|

| From BILLBOARD, November 21, 1964 |

Vee-Jay Records was virtually broke in spring 1966, three years after having been the first U.S. label to distribute the smash-selling records of the Beatles in the States. Ewart Abner, who had returned to Vee-Jay as general manager, saw the end of the company written on the wall and thus in 1965 started releasing Vee-Jay material on a new label. This label was called »Exodus«, a choice which does suggest either unwanted irony or conscious cynicism on the part of Abner. However, it seems that Abner managed the new label pretty secretively because as late as August 1966, when Vee-Jay was dissolved by court order, the employees of the company had never heard of »Exodus« (according to the account by Mike Callahan and David Ewards; the story as told in Robert Pruter's nonetheless authoritative Chicago Soul, p. 44, differs in some respects).

In any case, production at »Exodus« never went smooth. There was already much chaos behind the doors of Vee-Jay before it stopped all activities in May 1966, and the secretive existence of Exodus certainly wasn't helpful either. Several albums were released on the Exodus label, but it is unknown whether all catalogue numbers really were ever produced or sold to the public. What is more, Exodus used, quite inconsistently, different label designs in the few months of its existence, and it commonly happened that mono recordings were sold as stereo or vice versa. And in a number of cases the cover provided wrong information about what you could actually hear on the records!

|

| Exodus LP # 316 (1966) |

Even on the label of side 2 the wrong track list is printed, repeating the list of the front cover. Thus the content of the LP was changed in the last moment when front cover and label had already been printed. Or, equally probable, the inconsistencies between the information as given on the front cover viz. the label and the actual content of the LP resulted from the general chaos and nobody really noticed the mistake:

What is not in dispute is that somebody messed with the content of the LP, for whatever reason: The two songs »Just Be True« and »Ain't That Loving You Baby« replaced both »Make It Easy On Yourself« and »Since I Don't Have You«. This change was, in all probability, a last-minute decision, and that is why you even can hear this on the LP. Several record researchers have noticed this, among them Ron Dawson who remarked: »The last track on one side was taken off (although still listed on the cover) and replaced. I forget what the tune was but the way it was placed on was a doozy! You could actually hear the tonearm dropping onto the record and then the song starts. What an operation!« This »last track« is »Ain't That Loving You Baby«. In the unusually long interval between »Just Be True« and »Ain't That Loving You Baby« you can indeed »hear the tonearm dropping«:

Jerry Butler & Betty Everett: »Ain't That Loving You Baby« from the Exodus LP # 316 (1966):

»Ain't That Loving You Baby« had been recorded back in 1964 in Chicago and released as B-side of the Vee-Jay single # 613, eventually reaching # 24 r&b. The song in itself is one of the most beautiful duets of Jerry Butler and Betty Everett, and arguably their most successful tune apart from »Let It Be Me«.

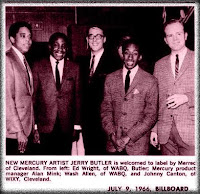

I don't know whether the Exodus LP »More of the Best of Jerry Butler« had any significant sales. In any case, this messy LP did not damage the career of the singer. His contract with Vee-Jay ended on May 31, 1966, and he then moved to Mercury Records. He was welcomed there with open arms and remained with Mercury for a number of years, starting a second successful career. Eventually he was to have more success at Mercury as ever in the time before 1967. In 1968, he landed a # 1 r&b hit with »Hey Western Union Man«, followed in 1969 by »Only The Strong Survive«.

In the following you can hear two more songs from the 1966 Exodus LP, »Need To Belong« (recorded back in 1963 and released on Vee-Jay # 567, r&b # 02 in spring 1964) and »Strawberries« (recorded in Chicago in 1962 and released on Vee-Jay # 526). Unfortunately, the sound quality is not excellent.

I can't hear the schmaltzy ballad »Need To Belong« too often at one time. The general public, however, has a different taste, and this song, written by Jerry Butler's buddy Curtis Mayfield, has become one of his better-known tunes. (Both Jerry and Curtis had been members of the Northern Jubilee Gospel Singers and the Impressions.)

»Strawberries« likewise has many fans. The lyrics are humorously romantic, and according to a critic of the Chicago Tribune »the song ... combines the lonesome cry of a street vendor and a lover's self-reassurance.« This cry »Strawberrrr-ries«, whose final syllable »-rrrries« is chirruped by Jerry Butler into the highest octave, faintly reminds me of Elvis Presley's »Crawfish« from the movie »King Creole«. Peter Guralnick called this song »interesting« (Last Train to Memphis: The Rise of Elvis Presley, London 1995, p. 449), and it almost does seem no coincidence that also a Billboard critic (in the issue of March 16, 1963, p. 34) took recourse to this adjective when he called Jerry Butler's West Indies-based »Strawberries« »interesting«. And as it is, calling a song »interesting« pretty much sounds like giving a polite compliment to an inept cook. What Jerry Butler thought of the song is unknown, but it isn't mentioned in his autobiography Only The Strong Survive. Memoirs of a Soul Survivor (Bloomington 2000). Nor is the Exodus LP »More of the Best of ...« which is even lacking in the closing discography ... for a reason, I guess.

Jerry Butler: »Need To Belong« / »Strawberries« from the Exodus LP »More of The Best of ...« (1966):

.jpg)